Overview

As today’s vulnerable populations present with more complexities, designing care models and identifying the appropriate multidisciplinary resource mix is key to delivering integrated, member-centered, outcomes-based care. As the health care industry continues to recognize the need for holistic care that meets the objectives of the Quadruple aim while addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH), many organizations find themselves awash in data sourced from disparate systems, representative of disparate aspects of care.

Understanding how to design a care model that leverages the right data to inform the design, implementation and monitoring of care teams, member and population outcomes and organizational bottom lines is a core component of population health management for complex individuals. Similarly, convening the right internal and external stakeholders to oversee and govern such a model, and designing an integrated care team to deliver this care, is a tall order. In this paper, we will discuss a sustainable and scalable method to leverage data to develop and implement care teams that address whole-person care across the care continuum.

Growth in Vulnerable Populations: Dually Eligible Beneficiaries

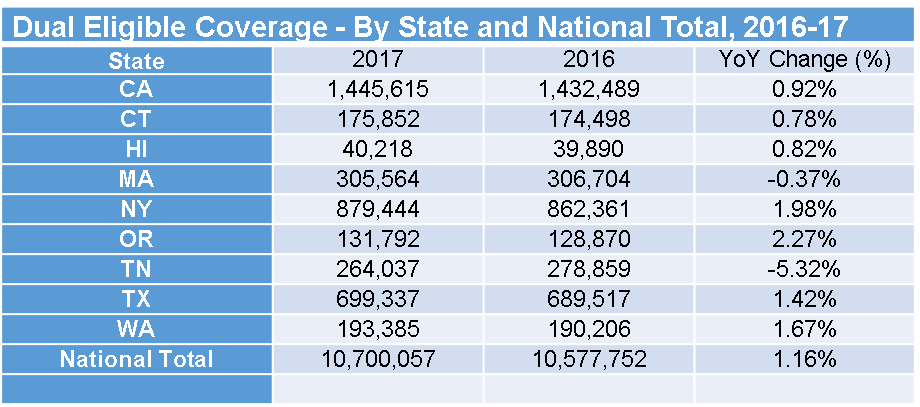

The prevalence and incidence of illness and co-occurring disorders alongside the impact of housing, food insecurity, and trauma all contribute to the holistic health of Americans. In recent years, addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) has proven to reduce health care spending; for example, Bradley et al., reported that states with a higher ratio of social service spending to total Medicare and Medicaid spending had better health outcomes for a variety of measures including reduced mortality from lung cancer1. Historically, total health expenditures for dually eligible beneficiaries (DEB) are much higher than those of Medicare-only beneficiaries. In 2017, it was reported a total of 10,700,057 were enrolled for DEB, up 1.16% from 2016 at 10,577,752. According to an analysis of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data by the HIR, Americans over the age of 65 struggle with finding basic transportation, which accounts for almost $18 million of total direct spending on health care2,3. Consumers with fair or poor mental health status were also responsible for $100 billion in direct health care spending4. The total DEB population ages 65 and older currently sits at 5,900,989, representing a combined Medicare and Medicaid spending of almost $200 billion5.

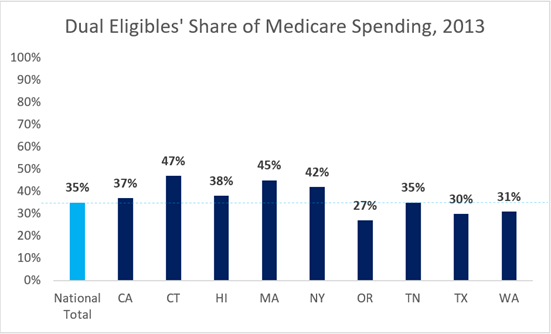

The figures below show the growth across a few states for the DEB population and their associated percentage of spend. Although the data timeframes do not coincide, one could extrapolate that the rather slow growth in the number and percentage of duals aligns with a rather higher percentage of health care spend in these states.

The prevalence of comorbid medical conditions that drive dual-eligible share of spending are complicated by the impact of housing, food insecurity and trauma. Identifying the appropriate balance of initiatives, interventions and resourcing to recognize, treat and manage in a comprehensive, longitudinal manner is not a simple math equation. Staffing models, case-loads, workflows and overall care model should be developed based on evidence-based care models but tailored to the specific population.

Key Drivers of Success for Care Model Build and Design

Whole-Person Approach

Building a framework and approach to care model design that takes into account the complexities of inter- and intra-organizational stakeholders and population-specific data is a critical driver of success. This approach considers the realities of delivering on the Quadruple Aim with the rigor of population health analysis and financial sustainability. The approach should be holistic and incorporate examples of best practices that extend into the community using support roles, such as, community health workers, peer supports, and other non-clinical providers to reduce and remove real and imagined barriers and limit the impact of social determinants of health.

Data-Driven, Member-Centered Design

The member is at the center of any successful model of care. Before designing a care model, one must understand the profile of members at a population level. When designing workflows around such members, there needs to be deliberate efforts to know each individual member, with close attention to identifying those with complex needs. Understanding their social, economic, psychological and physical prior, current and future states will help you develop, implement and re-assess the adequacy of your care model. Some considerations include:

- Is your care model informed using population level claims data analytics, supported by additional SDOH and clinical data as available?

- Have you developed dashboards that identify opportunities to address potential and actual gaps in care and spikes in utilization?

- Are you able to forecast or trend patterns of behavior relative to utilization?

- Are there opportunities that show up in the data that align with a type of care team member’s role and workflow?

All of these are considerations that play into the framework and approach for a care team.

Integrated Care Team

Care plans and care models should incorporate clear roles and integration points for the provider network as care at the end of the day must be physician-directed. Both the member and physician are clearly key drivers of a successful care model, care cannot simply be managed around them. The scope of the care team, their roles, and scopes of practice, methods and cadence of communication with both the member and the physician directly impact the type and frequency of utilization. Determining how best to manage established panels, review data and dashboards, update care plans and integrate those workflows into care team operations are attributes of the model you design for both your member and your provider network.

Cross-functional Leadership

The past decade has marked monumental shifts in the health care industry. It is no surprise that most health care organizations are not inherently designed to operationalize value-based care. Care models are central to success under value-based payment, as it is the means by which value is driven. Historically, clinical best practice was the standard for care models, designed and implemented by clinicians, often siloed from the rest of the organization. Looking toward the future, clinical best practice is a necessary but insufficient element of care model design; the operational and governance infrastructure of an organization has to evolve across functions for a far more integrated approach. Clinical leadership must work in concert with an empowered member and non-clinical partners in care delivery. Care model design at this stage, for many organizations, is truly an organizational redesign and community-level population health management planning.

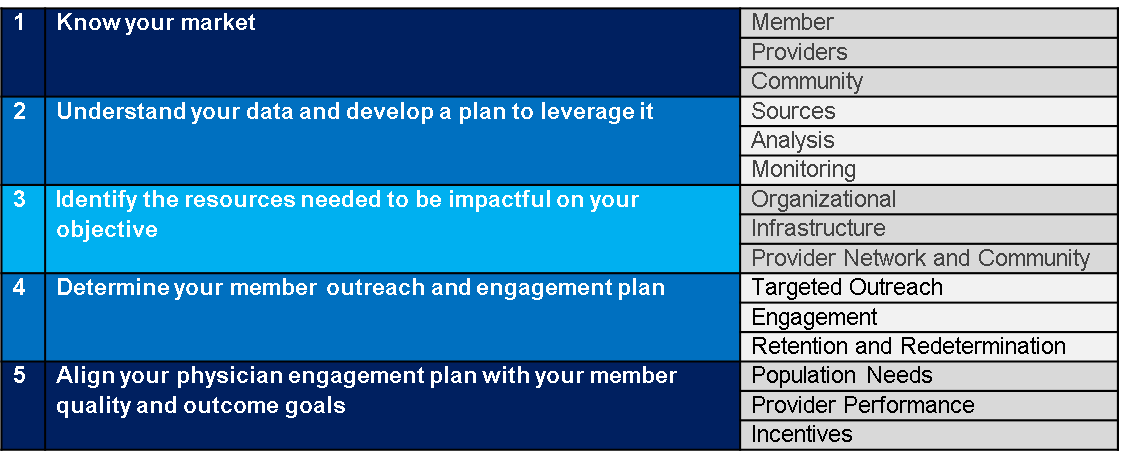

Five Considerations in Care Model Design and Implementation

Developing a sustainable and scalable method to leverage data to develop and implement care teams that address whole-person care across the care continuum is critical in managing the health of today’s dual eligible. The key drivers of success for care model build and design highlighted above help organizations optimize resources and improve outcomes for members, physicians and community partners. As health care continues to move toward value-based care, developing these types of care models can help organizations meet the Quadruple AIM.

Endnotes

1 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0814

2 https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/

3 https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/pdf/CMS-expands-MA-social-determinants_PwC_Jan2019.pdf

4 https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/pdf/CMS-expands-MA-social-determinants_PwC_Jan2019.pdf

5 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/StateProfiles.htm