How quickly can a health care market shift from traditional fee-for-service to payments based on value? New York state has a worthy but ambitious goal of moving 80-90% of managed care organization Medicaid expenditures to value-based payment (VBP) by 2020. In order to accomplish this, the state is using a carrot and stick approach with managed care organizations (MCOs) and providers by providing monetary benefits and penalties for meeting certain milestones on the path to achieving value based payment. In doing so, the state is intentionally disrupting the balance of power between providers and MCOs. So, what does this mean for providers and, particularly, small providers?

How quickly can a health care market shift from traditional fee-for-service to payments based on value? New York state has a worthy but ambitious goal of moving 80-90% of managed care organization Medicaid expenditures to value-based payment (VBP) by 2020. In order to accomplish this, the state is using a carrot and stick approach with managed care organizations (MCOs) and providers by providing monetary benefits and penalties for meeting certain milestones on the path to achieving value based payment. In doing so, the state is intentionally disrupting the balance of power between providers and MCOs. So, what does this mean for providers and, particularly, small providers?

Medicaid Reimbursement and the Role of DSRIP in New York

New York state, like the majority of states, currently provides a per member per month (PMPM) fee to MCOs in exchange for managing its Medicaid members and provider network. MCOs have traditionally paid fee-for-service (FFS) and variations on FFS to providers. Under traditional FFS contracts, MCOs carry the burden of risk, including member health and utilization, pricing and business acumen, and providers are paid for services rendered. In order to improve the quality and cost of care, the state wants MCOs and providers to transition to VBP arrangements in which providers will be at greater risk for managing the cost of member care, but also share greater financial rewards for providing more efficient, quality care. However, there may be insufficient market incentive for MCOs and providers to shift potential financial rewards and losses to providers.

In order for providers to benefit from an improvement in the quality and cost of care, they must enter into VBP contracts with MCOs. The challenge for the state is that there is little financial incentive for providers to adopt VBP arrangements when current provider contracts largely pay for the volume of services rendered, not value. Under these arrangements, if providers become more efficient and keep people out of the hospital, they will be paid less than they were before. In order for providers to successfully execute VBP contracts, providers must expend capital to build infrastructure in and out of the hospital, engage clinicians and learn new ways to manage cost and quality of care. This creates the oft-expressed concern of ‘having one foot in each canoe’ as revenue remains largely tied to FFS contracts, while care management processes and infrastructure are being built for VBP contracts.

This conundrum for providers may make it paradoxical to decrease the cost of care and volume of services rendered if the VBP contracts and efficiency rewards are not in place to replace lost revenue from inpatient stays. On the other hand, a lag in rewarding efficient providers through VBP allows PMPM-paid MCOs to profit from decreased inpatient utilization under traditional FFS payment arrangements.

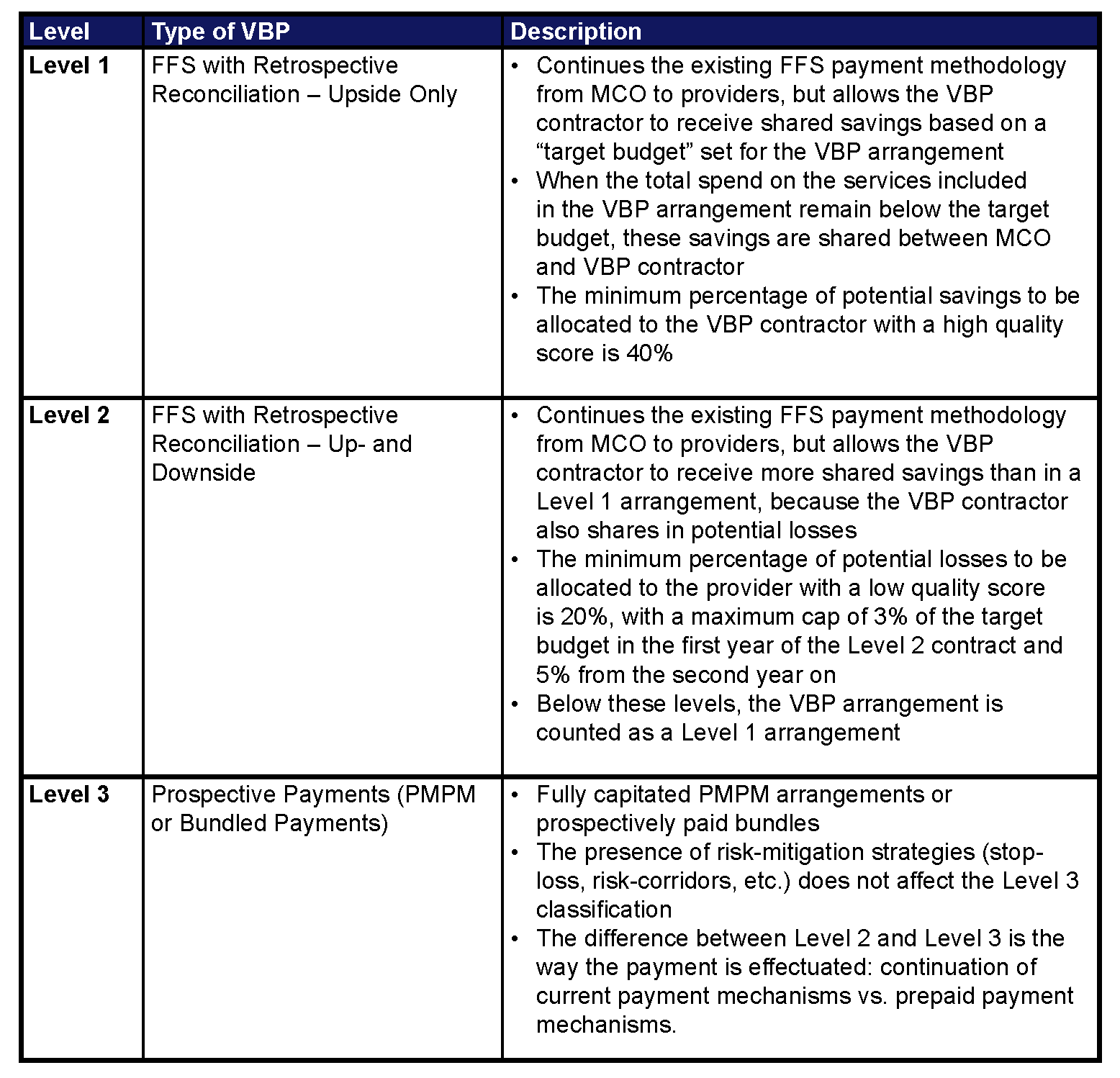

Therefore, the state is using the five-year Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP)1 program funds and policies to help bolster providers’ revenue during their conversion from FFS to VBP and spur MCOs to adopt higher level VBP arrangements. During the transition period of provider payment from FFS to a fully capitated payment model, there are several state-defined levels2 of VBP contracts to help ease providers into managing risk, such as FFS contracts with a shared savings component and FFS contracts with retrospective up- and downside adjustments. As providers take on risk for their Medicaid members, they will be eligible for greater rewards from decreasing their cost and increasing their quality of care.

VBP Requirements and Penalties for MCOs under DSRIP

To help close this gap in provider revenue during this transition period and encourage the necessary infrastructure investments anchoring a system-wide transformation to VBP, the state and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are investing $8 billion through a budget-neutral Medicaid Waiver program. $6.42 billion of these funds will be invested through the DSRIP program, which aims to decrease avoidable hospital use by 25% and increase the percentage of total managed care payments under VBP arrangements to 80-90% by April 2020. In order to communicate best practices and lessons learned throughout the state’s transition to VBP, the state has published the June 2016 New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform (the ‘Roadmap’)3, which will be updated annually.

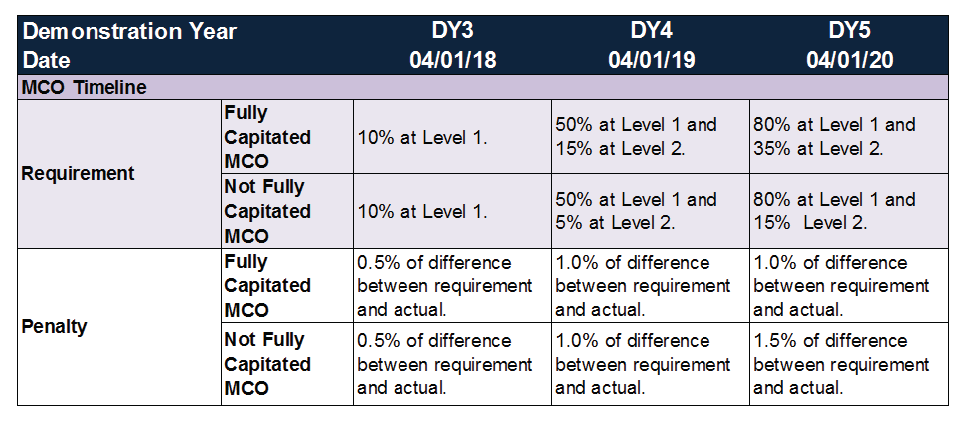

Under the June 2016 Roadmap update, MCOs are required to have 10% of total Medicaid expenditures in VBP level 1 contracts in 2018, increasing to 50% in 2019 and 80% in 2020. If MCOs fail to meet these hurdles, then they will be subject to a penalty based on the difference between the state’s goal for the year and the actual percent contracted. This penalty begins at 0.5% of the difference in 2018 and increases to 1.5% in 2020, depending on the capitation level of the MCO. (For additional detail, refer to the MCO VBP requirements and penalties chart and VBP contract levels in the appendix.)

New Incentives: Stick or Passing the Torch?

As noted above, as New York state’s health care system transitions to value over volume, a decrease in utilization and increase in efficiency will immediately benefit PMPM-paid MCOs and hurt the bottom lines of FFS-paid providers. Unless and until both convert to higher levels of VBP arrangements, all of the financial value of efficiencies inure to Medicaid payors, such as MCOs. This harsh reality might discourage provider innovation and risk assumption.

Under the June 2016 Roadmap, the state has propelled MCOs to transition to VBP contracts with a carrot and stick approach. MCOs with more provider-payment dollars in higher-level VBP arrangements will receive a stimulus adjustment4, while MCOs that fail to meet the state VBP goals will be penalized with a fee. To protect the MCOs from penalties due to recalcitrant providers who are unwilling to enter these higher-risk VBP arrangements, the state will allow MCOs to pass their penalties on to providers, with the intent of stimulating greater adoption of VBP contracts.

However, it is unclear if the penalties from the state are actually a “stick” over MCOs or if these penalties are providing MCOs with greater negotiating leverage in dictating unfavorable contract terms to inexperienced providers. This new regulation gives significant bargaining power to the MCOs in negotiations with providers and gives cause for small providers to seek refuge, most likely in large independent practice associations (IPAs) or accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Pass Down Penalties: Who’s Eligible and Who’s Not?

Whether or not providers will be subject to VBP penalties passed down from MCOs depends on two factors: 1) whether providers contract a “sufficient” portion of their MCO revenue in VBP arrangements to not be considered “unwilling” and 2) whether MCOs achieve their VBP contracting goals.

The state’s standard of “sufficient” MCO revenue in VBP as it is currently written in the June 2016 Roadmap is vague and remains to be tested. The state has developed a VBP contract review process and guidelines in order to help balance the scales of power between the MCOs and providers; however, these will continue to evolve throughout the DSRIP waiver period, based in no small part on good or bad market experience.

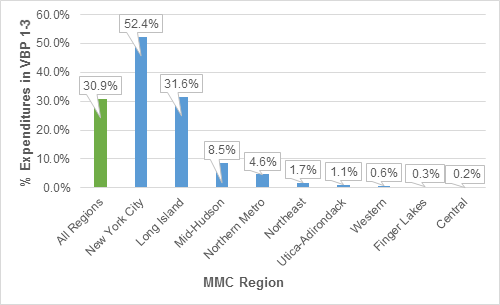

The more concrete requirement is whether or not MCOs have met their VBP requirements. Per the chart below from the state’s 2014 Medicaid MCOs VBP Baseline Survey Results5, there is great variance across the state in how close MCOs are to achieving their first VBP requirement of 10% of expenditures in level 1 or higher VBP contracts by April 2018. On an aggregate basis, New York City and Long Island have already exceeded this requirement, but all other regions still have a significant gap to fill in order to meet the state’s timeline.

Figure 1: Percent of Total Expenditures for Mainstrem Managed Care Plans in CY 20146

The Challenge for Providers to Navigate VBP Under DSRIP

The process for providers to successfully enter into these agreements is not a straightforward analysis. For one thing, under New York’s DSRIP, provider hospitals, health systems, clinicians, clinics and community-based organizations have formed 25 performing provider systems (PPS), which are provider networks that have contracted amongst themselves to collaborate on DSRIP projects. While Medicaid PPSs are seen as the main provider vehicle to ensure the state achieves its DSRIP goals, a PPS is not necessarily structured as a legal contracting entity, such as a messenger model IPA. In order to be a legal contracting entity, a PPS must form an IPA or ACO. Otherwise, providers can contract with MCOs directly as individual providers or through subcontracts with other providers. Therefore, not all PPSs can enter into VBP contracts on behalf of their partners in order to meet the VBP requirements for MCOs, without risk of running afoul of antitrust and other regulations.

In this environment, while all providers may find themselves at a disadvantage at the bargaining table, small providers have additional challenges to overcome in order to excel in VBP arrangements. Small providers contribute less to total MCO expenditures, and thus have considerably less impact on whether or not MCOs achieve their VBP goals. Smaller providers are, therefore, a less significant partner for MCOs in VBP contract negotiations. An even greater challenge for small providers, physicians and other practices, is that their smaller revenue volume also makes it more difficult for them to absorb swings in member utilization and to invest in the data analytics and infrastructure necessary to manage the risk of higher level VBP arrangements.

For small providers, successfully contracting any level of VBP arrangement independently may seem formidable (and oversight of these risk arrangements should be of concern to policymakers). Nevertheless, small providers are subject to the same VBP contracting penalties as all other providers, at the MCOs’ discretion, and must find a way to excel in VBP arrangements. To address the threat of VBP penalties being passed down to them through MCOs, smaller providers might feel strong pressure to consolidate or sign undesirable VBP contracts, which is a highly short-term strategy.

Recommendations for Small Providers to Successfully Transition to VBP

In order to ease the risk and administrative burden on small providers and prevent them from entering into impulsive provider partnerships, it may be advantageous for them to join an IPA or ACO anchored in a larger hospital system. Hospital-anchored IPAs and ACOs are large enough to absorb the risk of member utilization and have sufficient economies of scale to justify the investment in data and health information technology (IT) infrastructure that the transition to VBP arrangements necessitates. Currently, most DSRIP PPSs are investing in IT infrastructure and starting to educate their provider partners on the transition to VBP from both a clinical and administrative perspective. However, unless the providers in a PPS form an IPA or ACO, that partnership, education and collaboration might dwindle when the waiver period ends.

In addition to providing a structure of governance for coordinating member care and sharing risk, a larger IPA or ACO is a more significant partner with which to contract for MCOs. Since large IPAs and ACOs encompass a greater percentage of MCO expenditures, they have greater bargaining power and are able to incentivize MCOs to collaborate with them. Additionally, so long as these IPAs and MCOs share risk or are significantly clinically integrated, they may avoid antitrust concerns.

What Lies Ahead on the VBP Roadmap

As providers, regulators and payors learn from their experience in DSRIP projects and VBP contracts, updates to the Roadmap will communicate and adjust to these shared lessons and the state requirements may change. However, as the state gets closer to the end of the waiver period in March 2020, there will be additional pressure on MCOs and providers to engage in VBP contracts to achieve the state’s goal of 80-90% of MCO payments to providers in VBP arrangements. Some small providers may be successful in Level 1 VBP arrangements (FFS payment with shared savings), but in order to transition to higher level VBP contracts, they will need the capabilities and infrastructure of the larger health systems. Whether this impetus to further market consolidation yields the ultimate prize of lower health system costs remains an open question.

About COPE Health Solutions

COPE Health Solutions has expertise in performance-based contracting and IPA development. We work with health systems to help them better align financial incentives around clinical processes in order to capture capitated dollars and make improvements in quality and cost. Our team can help your health system, physician group, or clinic with strategic planning and decision making that includes determining whether to join or create an independent physician association (IPA), as well as how to successfully do so.

For more information about COPE Health Solutions’ Managed Care Systems Design services, please contact info@copehealthsolutions.com.

Source: http://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/2016/docs/2016-jun_annual_update.pdf

Appendix:

Table 1: VBP Levels as defined by the State

Table 2: MCO VBP Requirements and Penalties Under DSRIP8

Footnotes:

1DSRIP is part of the national federal and state 1115 Medicaid Waiver program and provides additional funds to providers in a performing provider system outside of ordinary Medicaid in order to undergird the system transformation. Other states have implemented DSRIP programs, including California and Texas. See the NYSDOH website for more information: http://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/overview.htm.

2Table 1 in the Appendix or Appendix X of the 2016 Annual Update to the New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform.

3http://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/2016/docs/2016-jun_annual_update.pdf

4MCOs that have captured more dollars in VBP arrangements will receive an increased capitation rate in 2018 (the ‘stimulus adjustment’). See page 44 of the Roadmap for the full definition: http://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/dsrip/2016/docs/2016-jun_annual_update.pdf

7Appendix X of the 2016 Annual Update to the New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform

8Pages 45-46 of the 2016 Annual Update to the New York State Roadmap for Medicaid Payment Reform