New York State’s (NYS) Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, a component of the NYS Department of Health’s (DOH) 1115 Medicaid Waiver, provides a unique opportunity for providers to invest in the delivery system and financial incentive transformation required for long term financial sustainability in a population health management business model. The DSRIP program requires the development of Performing Provider Systems (PPSs), geographically integrated networks of care for the Medicaid population. As part of the overall effort to redesign the Medicaid program through implementation of DSRIP, NYS DOH has also developed a value based payment (VBP) roadmap, updated annually, to reach its goal of 80-90% of by the end of DSRIP demonstration year (DY) 5. The Roadmap includes the VBP Innovator program, a voluntary program that will provide PPSs with up to 95% of the dollars paid by NYS to the MCO for total cost of care to providers leading the way in value-based payment arrangements and willing to take full risk for Medicaid members. The VBP Innovator program incentivizes providers already mature in their contracting to ready their newly formed PPS network for VBP contracts.

The transition to VBP for providers is complicated by:

- The current lack of adequate care coordination (warm hand-offs) and information sharing across providers

- The lack of access to lower-acuity care, such as after-hours primary care

- Inconsistency in how clinical outcomes are tied to VBP contract payments from one health plan to another

- The limited ability to obtain timely outcomes data required to make real-time UM decisions and course corrections across a large provider network

- The current dominant FFS model, through which most providers in NYS still are still rewarded for providing high volume of care rather than outcome-oriented care

- The lack of health plan willingness to engage provider networks and IPAs in negotiations for reasonably priced and structured VBP contracts.

The NYS DSRIP program is designed to mitigate many of the above challenges. NYS DOHs’ focus on VBP should encourage PPS’, providers and health systems to look at the DSRIP dollars as an investment in readiness for VBP contracts that will likely need to be coordinated through an independent physician association (IPA), rather than just an infusion of dollars to support DSRIP project implementation. The linkage of DSRIP funds to VBP transformation is truly a unique opportunity for providers to ensure they receive adequate premium dollars to fund the necessary care management and related systems required to improve quality outcomes and reduce global spend for large populations.

As each PPS is required to have defined contracting periods with partners participating in their PPS, it is critical that PPS leaders use each contracting period as an opportunity to design a network of care ready for VBP arrangements by designing escalating process metrics to drive transformation of the network and outcome metrics. NYS DOH has shared that performance measures for the VBP Innovator Program will be aligned with existing DSRIP measures, further incentivizing the importance of building processes that drive successful completion of these outcome measures. Process metrics (backed by a percentage of total dollars allocated to each partner and designed with long-term network success in mind) can be a meaningful way to encourage providers to implement practice changes needed to overcome some of challenges within the network and produce sustainable quality outcomes. NYS DOH realizes that to maintain success earned by the DSRIP program, payment reform to support better-coordinated care will also need to take place.

Translating Workflows into Process Metrics

PPSs should engage providers in designing critical workflows that can be translated into process metrics.

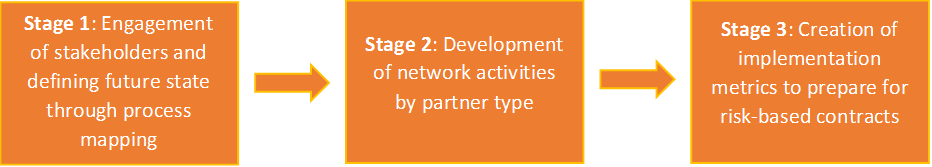

This process can be broken down into the following steps:

Stage 1: Defining Future State Through Process Mapping

Engaging providers through process mapping to identify care workflows was described in a previous Health Insights by Alex Trombetta and Auroop Roy of COPE Health Solutions and can be found here. These maps can serve to illustrate the vision for future implementation and guide the development of implementation metric creation as described below.

Stage 2: Development of Network Activities

Although these process maps may be workflow specific (i.e., a process map may illustrate the flow of a patient in the ED to assignment of care navigation resources to reduce unnecessary ED volume), process maps of several key workflows can be used as an input to identify key activities by partner type within a network. To do this, activities are created by analyzing the swim lanes of a process map and identifying future state roles by provider type. For example, in a process map illustrating the patient flow for an ED care triage program, examples of provider activities could be:

- Hospital EDs: Identify patients meeting criteria for care navigation; refer patient to care navigator; schedule patient for follow up with PCP

- PCP: Identify patients who no-show for appointments scheduled from ED and attempt to contact; create partnerships with hospitals to allow open access scheduling from the ED

Through the identification of activities across several workflows, a larger roles and responsibilities document that begins to inform provider type responsibilities across a network can be created. These activities can help communicate to each partner type their future role in the network and within a specific workflow and identify partner types for which the PPS needs to define future state network activities.

In addition to the roles and responsibilities document described above by analyzing processes, it is critical to consider activities that should be achieved under risk-based arrangements. For example, outside of process mapped workflows, skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) may play a key role in a future network and will need to accept direct admits easily from the ED or PCPs to reduce unnecessary hospitalizations. The activities list developed from process maps should be built upon to include key activities for all partner types across the network.

Stage 3: Creation of implementation metrics to support risk-based contracts

Implementation metrics can be created by identifying a priority list of outcomes that the network wants to impact and using the above mentioned activities list to create implementation metrics that can be prioritized for payment in DSRIP partner contracts. Implementation metrics developed over several contracting periods should gradually enable networks to manage members in capitated contracts by:

- Ensuring the right network of providers

- Closing gaps by role to enable success by partner roles (partner roles to be developed in the above mentioned roles and responsibilities document)

- Preparing for utilization changes and reducing utilization

- Reinforcing quality

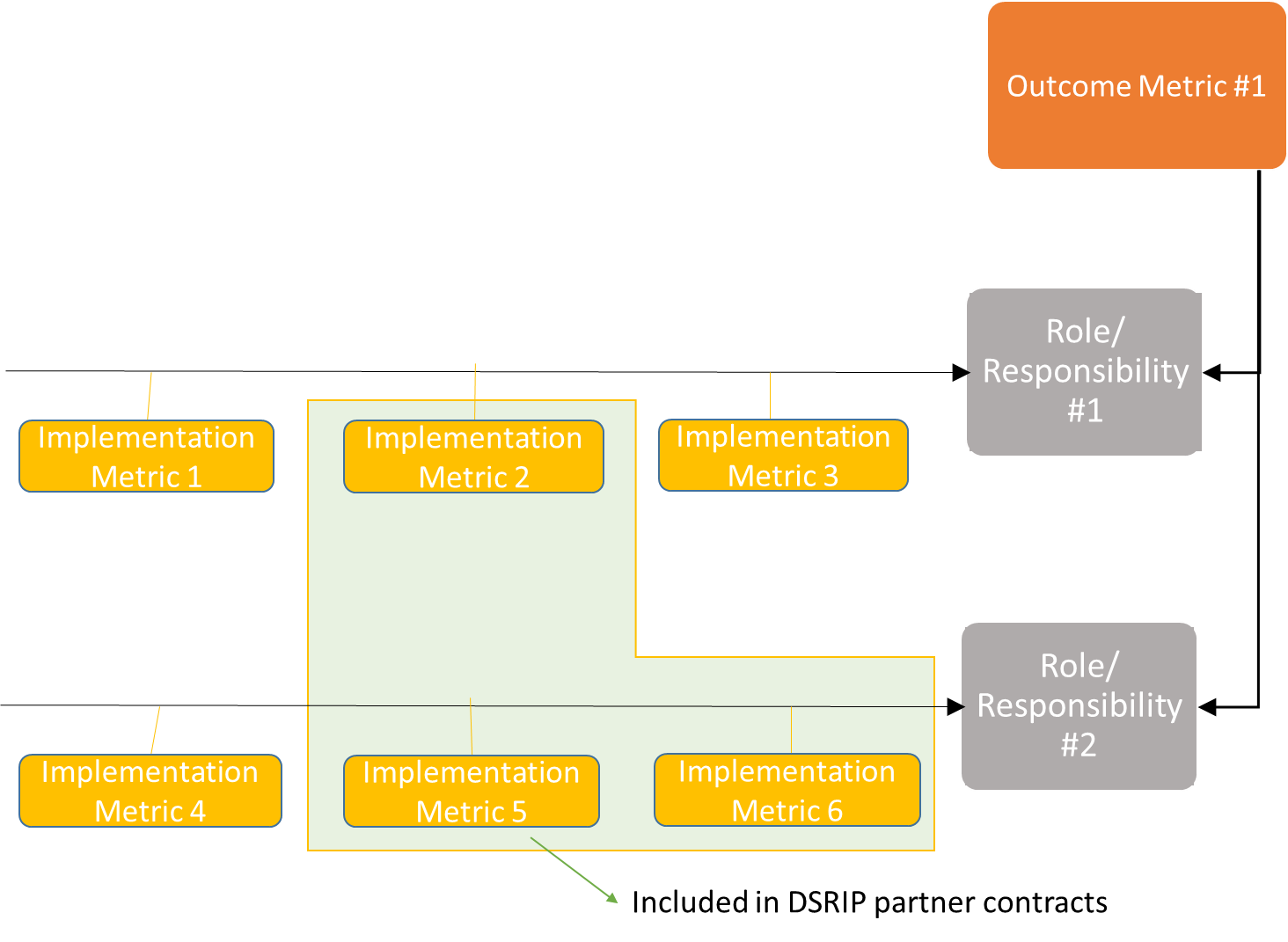

These metrics should be specific, time-bound, determined to be valuable and sustainable under future risk-based payment contracts and aligned with outcome metrics found to be valuable in the future network. Taking a top-down approach to alignment with outcome metrics critical for success can enable alignment and prioritization of outcomes, activities and metrics. The diagram below provides an illustration of how an outcome metric defined as critical may translate from a network activity to an implementation metric.

Only implementation metrics determined to be most critical to achieving outcomes and transformation should be included in the DSRIP partner contracts for payment.

Preparing for Potential Challenges

While developing implementation metrics to drive change across a network, there may be challenges stemming from creating metrics that are applicable to providers with differing levels of sophistication, balancing the needs of different stakeholders and the reporting burden for both providers and the PPS.

It can be difficult to create implementation metrics that apply to all providers, even those of the same type (i.e. primary care physicians), as providers of the same type may vary significantly based on scale, types of care provided and readiness. For example, a large federally qualified health center already on the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) certification journey will be much better able to implement open access scheduling than a small practice without sophisticated scheduling tools. Collecting and agreeing on objective data to place providers at a certain level of readiness, potentially through a gap assessment, would allow implementation metrics to be assigned to ensure payment for improvement at all levels of readiness.

For example, providers can be placed on a readiness trajectory for PCMH of a 1-5 scale based on an objective gap assessment. Those who have already achieved PCMH certification would receive a 5 and implementation metrics appropriate to level 5 providers. Depending on the metric, readiness can be adjusted in both scale (i.e. increasing the percentage of patients requiring a care plan at each level), timeline (i.e. providers with level 1 readiness have an elongated due date for identifying patients in need of a care plan) or a combination of both (i.e. level 1 providers are responsible for identifying patients in need of a care plan, level 4 providers must create a care plan for 50% of patients, while level 5 providers must create a care plan for 75% of eligible patients).

In addition, the total number of metrics and overall provider lift included within each DSRIP contract must be considered with the possible incentive amount. This can be balanced by identifying implementation metrics that drive the most change of outcomes desired or identified as most critical by stakeholders through the alignment exercise illustrated above.

Conclusion

The ability of the NYS PPS’ and other networks to utilize DSRIP dollars to design a network of care in a transparent, engaging fashion will determine success and ease of transition into future integrated delivery networks ready for VBP contracting with health plans. Using a structured approach similar to the one described above to redesign workflows and define provider roles can engage partners in the creation of a sustainable network and prepare partners to preform functions key to the future network. Utilizing DSRIP dollars to create incremental process metrics incentivizes providers and networks to make design and infrastructure changes now that will help develop the future integrated delivery network that can be successful contracting with health plans in risk contracts. By taking advantage of programs like the VBP Innovator program, PPSs that are successful in creating the integrated delivery network and VBP can capture additional dollars by taking full risk for members.

COPE Health Solutions’ nationally recognized team includes experts in care coordination, value-based payment contracting and the key population health management systems, business processes and contractual frameworks required for succeeding in delegated risk contracts with managed care organizations. Please contact us at info@copehealthsolutions.com to learn more.